Upcycling 'Fast Fashion' To Reduce Waste And Pollution

Upcycling 'Fast Fashion' To Reduce Waste And Pollution

Scientists, at the 253rd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS) have reported significant progress towards upcycling clothing.

"People don't want to spend much money on textiles anymore, but poor quality garments don't last," Simone Haslinger explains. "A small amount might be recycled as cleaning rags, but the rest ends up in landfills, where it degrades and releases carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas. Also, there isn't much arable land anymore for cotton fields, as we also have to produce food for a growing population."

All these reasons amount to a big incentive to recycle clothing, and some efforts are already underway, such as take-back programmes. But even industry representatives admit in news reports that only a small percentage gets recycled. Other initiatives shred used clothing and incorporate the fibres into carpets or other products. But Haslinger, a doctoral candidate at Aalto University in Finland, notes that this approach isn't ideal since the carpets will ultimately end up in landfills, too.

A better strategy, says Herbert Sixta, Ph.D., who heads the biorefineries research group at Aalto University, is to upcycle worn-out garments, "We want to not only recycle garments, but we want to really produce the best possible textiles, so that recycled fibres are even better than native fibres." But achieving this goal isn't simple. Cotton and other fibres are often blended with polyester in fabrics such as "cotton-polyester blends," which complicates processing.

Previous research showed that many ionic liquids can dissolve cellulose. But the resulting material couldn't then be re-used to make new fibres. Then about five years ago, Sixta's team found an ionic liquid - 1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]non-5-ene acetate - that could dissolve cellulose from wood pulp, producing a material that could be spun into fibres. Later testing showed that these fibres are stronger than commercially available viscose and feel similar to lyocell. Lyocell is also known by the brand name Tencel, which is a fibres favoured by eco-conscious designers because it's made of wood pulp.

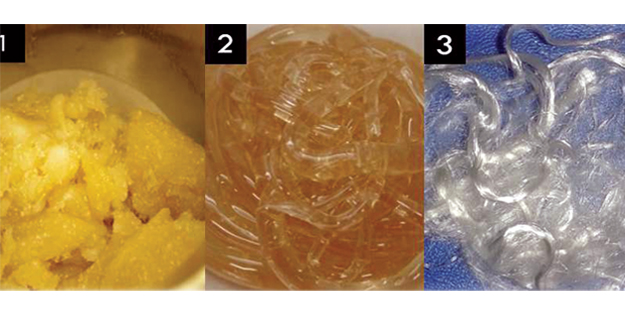

Building on this process, the researchers wanted to see if they could apply the same ionic liquid to cotton-polyester blends. In this case, the different properties of polyester and cellulose worked in their favour, Haslinger says. They were able to dissolve the cotton into a cellulose solution without affecting the polyester. "I could filter the polyester out after the cotton had dissolved," Haslinger says. "Then it was possible without any more processing steps to spin fibres out of the cellulose solution, which could then be used to make clothes."

To move their method closer to commercialisation, Sixta's team is testing whether the recovered polyester can also be spun back into usable fibres. In addition, the researchers are working to scale up the whole process and are investigating how to reuse dyes from discarded clothing.

But, Sixta notes, after a certain point, commercialising the process doesn't just require chemical know-how. "We can handle the science, but we might not know what dye was used, for example, because it's not labeled," he says. "You can't just feed all the material into the same process. Industry and policymakers have to work on the logistics. With all the rubbish piling up, it is in everyone's best interest to find a solution."

textileexcellence

textileexcellence